It’s been a weird year, ae? And now you’re busting to get back into the air. Just before you do, have a look at this summery (see what we did there?) of advice from past Vector magazines.

Let’s start with you

The safety of every flight hinges on your ability to make good decisions. Before taking off, be brutal in your assessment of how you’re feeling, both physically and mentally. Are you maybe off your game with a cold or the effects of new medication? What about fatigue? It’s a pretty tiring time of year. How about all those Christmas celebrations? You know this stuff affects your ability to make important decisions.

The build-up of stress can be pretty insidious. We often recognise it more easily in others than in ourselves. And the lead-up to Christmas, as we all know, is a stressful time. Add to that, the distress caused by COVID-19, and you wouldn’t be alone in finding yourself less than calm at this time of year. Read “Personal Preflight” in the July/August 2014 [PDF 2.7 MB] edition of Vector to get some tips on what you can do to reduce stress levels. Also check out our information on COVID-19 human factors considerations for more advice.

Remember the ‘I’M SAFE’ mnemonic to check off how safe you are to fly. You can email publications@caa.govt.nz for free copies of the I’M SAFE and ‘Are you fit to fly?’ posters.

Your airworthiness

If you haven’t flown for a while, you probably need to consider the currency of your paperwork – your pilot medical, and pilot licence or certificate. When’s your next BFR due? Remember to leave plenty of time to book one in. Even if it’s not due for a while, consider taking a dual flight with an instructor to refresh your skills. If you’re not current, what’s your plan to get there?

And think about your VNCs – they alter every November so make sure you have the latest edition. Apply to aipshop.co.nz(external link).

And now, the aircraft

It comes down to dust, dirt, guano and critters.

Your aircraft may have become home to a family of birds, particularly starlings. These skillful nest-builders can fill any open orifice on the aircraft with their nesting materials. Look particularly under engine cowls or in the fuselage. Nests pose a real danger to flight safety. They could cause an engine to overheat, catch fire, or seize. Nests built in the fuselage or wing can foul the control cables and could result in a control surface jamming.

Other wildlife may have decided on a new home in your aircraft. Rats and mice are occasional tenants in idle aircraft, and may do considerable damage to wiring, hoses and upholstery, in addition to building nests in hard-to-reach places.

Believe it or not, even something as substantial as a possum can adopt aircraft. One particular helicopter pilot recalls being startled on start-up when a possum appeared from the engine compartment and scrambled over the top of the canopy.

A host of things to check

Here’s what we told pilot operators to do when COVID-19 level 3 became level 2. The advice applies just as much to preflight checks before your first summer flight.

“First, and most obviously, check if the airframe/engine manufacturer requires any special maintenance following an extended period of non-operations.

Next, check for any outstanding calendar inspection or maintenance requirements that may now be overdue. It won’t be enough to just look at the tech log because some calendar requirements may not have been noted before the aircraft was parked up.

Examples could include two-yearly avionics inspections, ELT battery replacement, four-monthly oil replacement or a review of airworthiness.

As the aircraft owner/operator, make sure you review the airframe/engine logbooks to ensure nothing is missed.

Check that your maintenance controller is across whether airworthiness directives, service bulletins, and instructions for continued airworthiness apply. If so, they’ll need to be added to your maintenance programme. Some components may be due for calendar-time inspections, rather than in-service time. Better to think about these aspects while the aircraft is idle, rather than having to make short-notice arrangements.

Deal with the battery. And the oil. Give the engine a decent ground run to operating temperature before an oil change and operational check flight.

Double check all covers and blanks are removed. And check the tyres and landing gear struts are inflated correctly.”

Not wanting to lecture you on the basics, but those of you jumping back into gliders, paragliders, and other Part 149 aircraft, you’ll give them a good check-over ae?

Weather

Summer doesn’t mean relentlessly clear skies. The weather in New Zealand is always changeable and there can be strong and gusty winds, more pronounced sea breezes, aggressive thermals, and towering cumulus formations throughout summer – all with associated turbulence.

Always do a weather check as part of your flight planning. Use MetFlight GA(external link), and include the GRAFOR, AAW, TAFs, METARs, and SIGMETs in your considerations.

Combine these with your observations of actual conditions to form the ‘big picture’. For more information, refer to the VFR Met GAP booklet, or email publications@caa.govt.nz for a printed copy.

Temperature

Warm temperature is one of the reasons we like summer, but if not properly managed, heat can be debilitating. Some cockpits are notorious hothouses, so adequate ventilation – and hydration, see below – are important.

Warmth helps the grass grow, and what was short grass at a strip last week may well be a hazard this week. Braking action and take-off roll can be badly affected by long grass, and if the grass has gone to seed, be aware grass seeds can find their way just about anywhere, even into carburettors.

Also a heads-up that just because you’re flying on a beautiful day, the ground may not be as dry as you think it should be. You may need more space to land, and you should be aware that the length of the grass, and how wet it is, can affect the distance needed for both take-off and landings.

Extended hot weather may turn grass brown, and at some affected aerodromes, the boundaries of the usable runways or vectors may be, at first glance, hard to distinguish.

Daylight

Another often overlooked aspect of summer flying is time. Summer means long evenings, and part of that is due to New Zealand switching to daylight time in September until April. That means that during summer our time is 13 hours ahead of UTC rather than 12. That’s still a trap for even experienced pilots, so make sure you factor this in when making any flight plans, interpreting weather reports, and providing ETA or SAR times. Read “When a sunset isn’t pretty” in the Summer 2019/20 [PDF 3.3 MB] edition of Vector magazine.

If flying during the evening hours, do be aware of the cumulative effects of fatigue if you have been working at your regular job during the day.

Carburettor icing

Carburettor icing doesn’t just happen in cold weather. In fact, humid summer days are more of a risk than cold, clear winter days, because cold air holds less moisture than warm air. Carburettor icing should be expected when the outside air temperature is between –10°C and +30°C with high humidity and visible moisture present but is most likely between +10°C and +15°C, with a relative humidity above 40 percent.

You must use your knowledge and experience to identify carburettor icing – the closer the temperature and dewpoint readings, the greater the relative humidity.

It’s going to be busy up there

Summer weather will draw out other aviators like you, in all forms of aviation. Take particular note of your up-to-date charts of symbols for hang gliding areas, gliding areas and those for model aircraft. Look out for winching activities associated with these forms of aviation. Remember, however, all forms of gliding can be encountered in unmarked areas as well.

Be constantly alert for traffic – particularly in the vicinity of parachute landing areas. Not only will there be more intense activity, it may go on for longer with the extended daylight hours.

Remember the ADS-B grant scheme.

Check AIP Supplements and NOTAMs. Read the back cover of the Summer 2020/21 Vector for events held in areas that may be in temporarily restricted airspace.

Finally, watch the low-level flying. Check out 91.311. You might think this is a basic. But we’ve had a number of aviation-related concern reports from the public about alleged flying below 500 ft AGL.

Dehydration

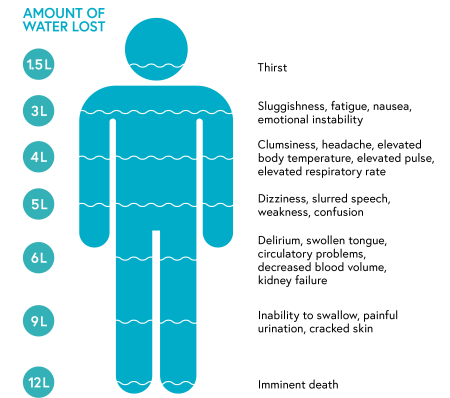

Don’t muck up all your great preparations by getting dehydrated in the higher temperatures. By the time you’re thirsty, you’re well on your way to dehydration. Its effects may have already begun to take hold – from just being hot and uncomfortably sweaty through to a decline in peripheral vision, and logical thinking.

The best way to keep hydrated is to eat and drink regularly and avoid diuretics like alcohol and caffeine. Drink about two litres of water every 24 hours. Make sure you’ve had a couple of glasses of water before you head off.

On warm or hot days, it’s especially important to be adequately hydrated, because you may quickly become dehydrated in a hot cabin environment. A useful article on hydration, “Need a Drink?”, can be found in the November/December 2005 [PDF 1 MB] edition of Vector.

We say it every year

We often get reports of incursions into temporary restricted areas, or of pilots landing on runways with work in progress, so the message is clear and simple: check NOTAMs and AIP Supplements before you take off.

How else will you know about that big hole in the surface of a runway, or that a flying competition is in progress?

Supps are issued to advise pilots of temporary restricted areas associated with events such as airshows and competitions, including those associated with model aircraft.

Temporary airspace associated with an emergency will be promulgated by NOTAM.

Checking both is an essential part of a preflight briefing.

Also think about updating your knowledge en route. Check with FISCOM that a new NOTAM has not been issued since you became airborne. It happens.